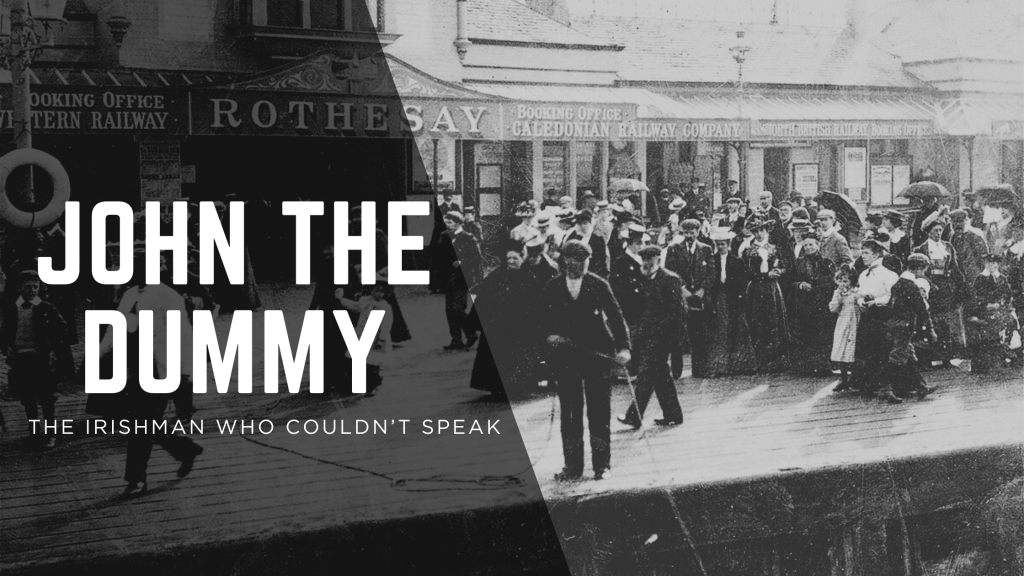

It’s the mid-1800s. You’re cruising down the Clyde on a crowded paddle steamer, the wind sharp with salt and coal smoke. As Rothesay pier comes into view, you’re warmly welcomed by the ripe aroma of seaweed and fish guts. The waterfront buzzes with noise — hawkers shouting, gulls circling, visitors spilling off the gangway in their Sunday best. And you? You almost lose your hat to an angry Rothesay seagull, and one stumbling man has just spilled ale on your frock. Some things never change.

Among the bustle of shopkeepers and sailors is a cast of unique local characters, people whose quirks and antics were once impossible to ignore, but whose names have long since slipped from island memory. Making my way through some dusty archives, I stumbled upon an article from 1913 dedicated to these famed locals of Bute. So, in the spirit of keeping their legacy alive, here are some of the characters you might have met if you stepped ashore in Rothesay at that time:

Named in the 1913 article as ‘John the Dummy’, John Elliot was described as a tall Irishman with a slightly mischievous charisma that made him a hit with local children selling good, old fashioned candied rock. ‘Salt and Whitning!’ he’d shout, clambering down Montague Street in a decorated donkey cart with a tin trumpet.

The children would run to the towering man dressed in a brown apron and a ‘lum’ hat (Scottish name for a top hat – lum meaning chimney), his cart kitted out in spinning rainbow-coloured windmills and flickering flags. I can’t help but get visions of the child catcher from Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

Yet despite his flamboyant charm, what made him so fascinating wasn’t what he said, but what he didn’t. When John first came to Bute, he passed himself off as unable to speak. There were suspicions amongst locals as to how true this was.

One day when John was in Kingarth Smiddy (yes, the building that’s still there today!), the patrons wanted to put John’s muteness to the test. So they got a hold of him, stripped the clothes off his back, and threatened to brand him with a red hot iron unless he spoke. The test was cruel and… successful, and according to the newspaper, “John shouted for mercy in name of all the saints in heaven.”

So, the next time you’re in Kingarth Hotel, listen for the faint, ghostly cry of an Irishman: “In the name of Michael, Mary, Joseph, Francis, Patrick…”

They just don’t make ’em like Bell anymore. Tall, stalwart, and impossible to miss, Bell Cod cut a striking figure along the Rothesay quay, smoke curling from her cutty pipe as she sold cockles, mussels, and whelks to anyone who crossed her path. Her sharp tongue and commanding presence made her Ladeside house a hub of nightly commotion — lodgers partied, neighbours shouted. As the 1913 article puts it, “the boys of the period used to derive no little amusement in the locality on such occasions”.

Yet behind the raucous exterior lay a woman of remarkable courage and kindness, earning her the title of ‘ministering angel’. When cholera struck the island, Bell Cod showed no fear of the disease, tending to the sick with determination and care. She concocted cooling drinks in her own kitchen, delivered them to the suffering, and assisted the authorities with tasks most refused to face in the outbreak.

Bell Cod embodied contrasts: a party animal by night and a heroic angel by day. We might have called her today something along the lines of The Fairy Codmother.

John Henderson, better known as Daft Jock, was depicted as a strong man with a childish laugh. Though some thought him simple and the newspaper even goes as far as to label him an ‘imbecile’, he often proved surprisingly clever, inventing hilarious solutions to everyday problems — whether using a cod tail as a brush to post bills or tinkling a piece of tin against a donkey’s wheel to speed the animal up.

John would also happily join in the pranks of Rothesay boys, though his temper could flare when crossed. It’s reported that in a fit of rage, John threw a piece of coal at the head of a young prankster, rendering him in a bad condition.

Tragedy and misjudgement also marked his life. After losing an arm in a granary accident, Jock was later sent to the asylum at Lochgilphead in a carefully orchestrated ruse that would rightly raise ethical concerns today. The local sheriff-officer convinced Jock to help transport a “daft man” to the institution, promising a free sail and a good dinner.

Trusting the plan, Jock boarded the steamer, only to discover that when two asylum attendants drew up in a cart, that he himself was the intended patient. Protestations that “it was the other man, not me, who was daft” were shouted in vain, and he was swiftly removed to the asylum. It’s a welcome relief to know that we’ve progressed in the understanding of mental health today.

For a bit of context, Argyll District Asylum was established in 1863 in Lochgilphead. It was the first district asylum in Scotland, set up under the Lunacy (Scotland) Act of 1857, which mandated the provision of care for the mentally ill. Though, we can safely assume that ‘care’ is a term to be used lightly for the time period.

Are you ready for this one? McDougall was a man who is said to have earned his nickname by selling sparrows which he had painted to resemble canaries. I can’t imagine the look on a ‘canary owners” faces when their birds would take a bath.

He was a famed conman on Bute, known for his salesman antics and fraud that would probably land him in jail these days. McDougall was a renowned storyteller, too. But only if it meant making himself a handsome profit.

Picking up odd jobs around the island in his free time, a young shop assistant was ‘prevailed upon’ by the ‘She-Canary’. He convinced the man to let him clip the ears of his little terrier dog with an old pair of scissors, and, apparently, infamously ruined the appearance of the poor thing for life.

McDougall was the least likeable of all the characters described, and people were said to be quite relieved when he took to pastures new on the mainland.

Just in time for hallowe’en, we have the spooky character of the ‘O’ man. I think what makes his character shrouded in terror was actually the fact that nobody knew anything about this man – not even his real name, which is always such a strange thing for a small town like Rothesay.

The ‘O’ man got his title from his strange behaviour of walking slowly and quietly along the street, then suddenly coming to a halt on a street corner, looking to the sky and crying in a long, loud drawn monosyllable ‘O’. A man of few words and one very loud, terrifying letter.

The ‘O’ man spoke to no one, adding to the town’s anxiety around his oddness. In fact, so much so, that though harmless, parents would use him to keep children in line, like he was Rothesay’s very own Bogeyman. “There’s the ‘O’ man. He’ll come and take you away!” they’d say to their naughty children.

“What inspired him to the habit of uttering his cry at intervals as he moved along, it is not easy to say, unless it was admiration of the wonders of nature as he gazed upwards,” says the 1913 article. I don’t know how much of that is true with Rothesay’s notorious grey overcast and West Coast showers.

This is a character that will pull at the cockles (or whelks) of your heart. At the head of the mid-pier, sat a solemn man, where, from a little stand, he sold whelks. Meet Peter Struggle.

How he came to be known by ‘struggle’ was actually deeply poetic and slightly nihilistic. My favourite combination. Before selling whelks, Peter owned a beer and porter cellar, just at the foot of Gallowgate. Over his door was a sign-board, which read “I struggle through the world”.

This phrase was illustrated by the picture of a globe, representing the earth, and through the globe, there was a figure of man with his head and shoulders seen through the upper end, and his feet dangling from the lower.

The newspaper surmises that this motto came from the fact that Peter only had one leg.

Did you enjoy this article? You can find more fascinating history and culture articles here at Features on Bute.

A note from me:

Features on Bute was a passion project I started 4 years ago as a love letter to my hometown. I pour hours into researching, writing, and sharing these Bute stories — sometimes travelling from Erskine to the Rothesay Museum, digging through archives, and covering the costs of images and media myself. Writing is my livelihood, so community support is always deeply appreciated. If you enjoy these stories and would like to help keep this work going, any donation — however small — makes a huge difference. Thank you for helping me keep Bute’s stories alive!

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.